ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED BY: HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH

(Harare) – Children and adults who work on Zimbabwe’s tobacco farms are facing serious risks to their health as well as labor abuses, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. Child labor and other human rights abuses on tobacco farms in Zimbabwe tarnish the tobacco industry’s contributions to the country’s economic growth and improved livelihoods.

The 105-page report, “A Bitter Harvest: Child Labor and Human Rights Abuses on Tobacco Farms in Zimbabwe,” documents how children work in hazardous conditions, performing tasks that threaten their health and safety or interfere with their education. Child workers are exposed to nicotine and toxic pesticides, and many suffer symptoms consistent with nicotine poisoning from handling tobacco leaves. Adults working on tobacco farms in Zimbabwe also face serious health risks and labor abuses.

“Zimbabwe’s government needs to take urgent steps to protect tobacco workers,” said Margaret Wurth, children’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch and co-author of the report. “Companies sourcing tobacco from Zimbabwe should ensure that they are not buying a crop produced by child workers sacrificing their health and education.”

Human Rights Watch conducted research in the four provinces responsible for nearly all of Zimbabwe’s tobacco production. The report is based on interviews with 125 small-scale tobacco farmers and hired workers, including children or former child workers, in late 2016 and early 2017. Human Rights Watch also analyzed laws and policies and reviewed other sources, including public health studies and government reports.

Human Rights Watch found that the government and companies have generally not provided workers with enough information, training, and equipment to protect themselves from nicotine poisoning and pesticide exposure. Human Rights Watch found similar conditions on tobacco farms in research in other countries, including the United States. But where governments have enacted strong laws against child labor, and provided extensive information about hazards and how to provide protection, such as in Brazil, there has been some progress in keeping children out of the fields and protecting other workers.

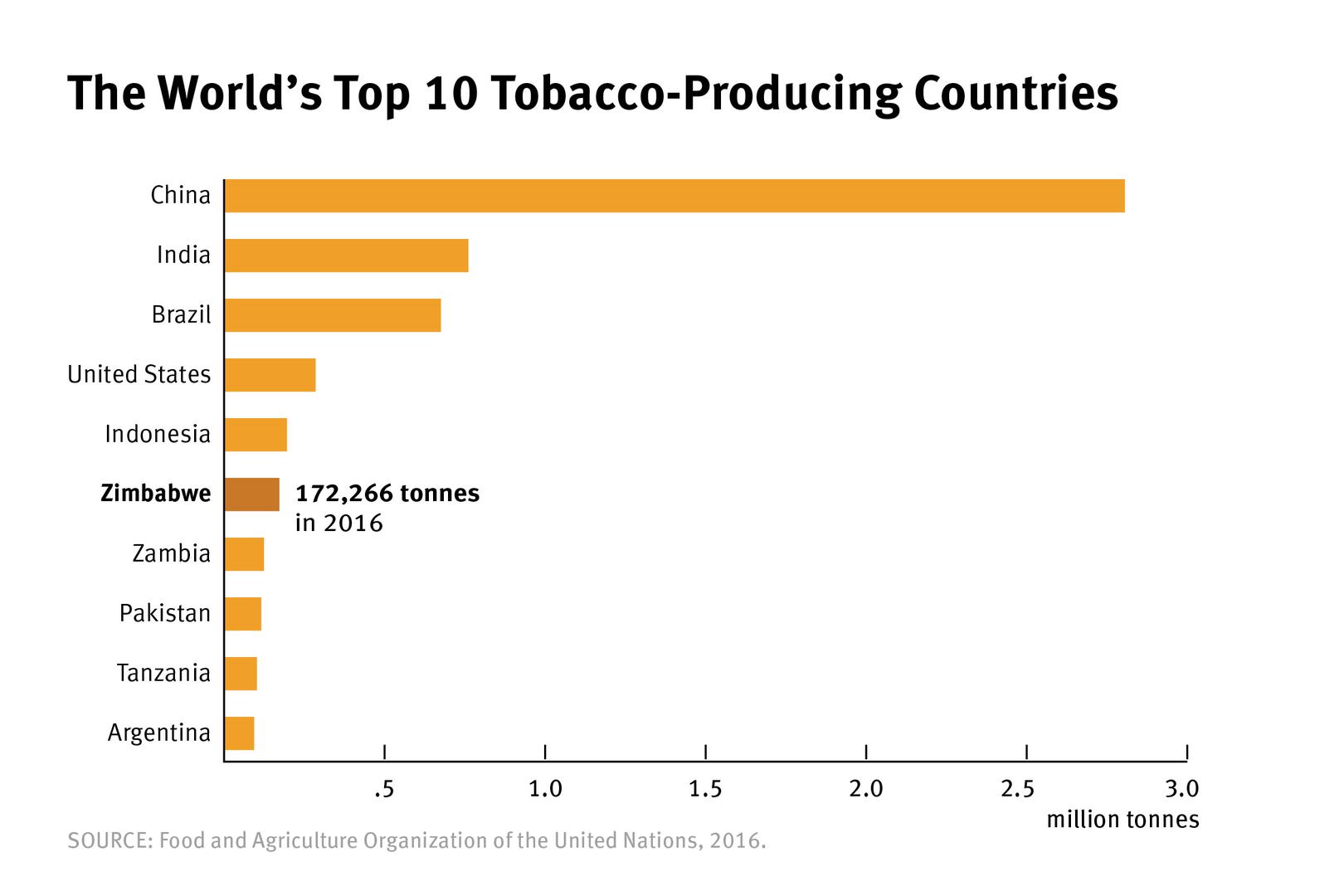

President Emmerson Mnangagwa, who replaced Robert Mugabe in November 2017 following military intervention, stated his administration’s economic policy would be based on agriculture. Zimbabwe is the world’s sixth-largest tobacco producer. The crop is the country’s most valuable export commodity, generating US$933 million in 2016.

Some of the world’s largest multinational tobacco companies purchase tobacco grown in Zimbabwe, either directly or at auction, including British American Tobacco, Japan Tobacco Group, and Imperial Brands. Under human rights norms, companies buying tobacco from Zimbabwe have a responsibility to ensure that their business operations do not contribute to child labor and other human rights abuses.

Human Rights Watch contacted the companies that collectively bought 86 percent of Zimbabwe’s tobacco in 2016. Most of the multinational companies involved have policies prohibiting their suppliers from using child labor and engaging in other human rights abuses, but Human Rights Watch’s findings suggest serious gaps in carrying out and monitoring these policies in Zimbabwe. Tobacco companies should explicitly prohibit direct contact by children with tobacco in any form, conduct regular and rigorous human rights monitoring in the supply chain, and report transparently on their findings, Human Rights Watch said.

One of the most serious health risks in tobacco farming is acute nicotine poisoning, or Green Tobacco Sickness, caused by absorbing nicotine through the skin from tobacco plants. The 14 child workers interviewed, and most of the adults, said they had experienced at least one symptom consistent with acute nicotine poisoning – nausea, vomiting, headaches, or dizziness – while handling tobacco.

“Davidzo,” a 15-year-old worker said, “The first day I started working in tobacco, that’s when I vomited.” He said he felt especially sick when he carried the harvested leaves. “I started to feel like I was spinning,” he said. “Since I started this [work], I always feel headaches and I feel dizzy.” The long-term effects have not been studied, but research on smoking suggests that nicotine exposure during childhood and adolescence may affect brain development.

Zimbabwean law sets 16 as the minimum age for employment and prohibits children under 18 from performing hazardous work, but does not specifically ban children from handling tobacco. The labor ministry told Human Rights Watch that it had not documented any cases of child labor in the tobacco industry.

Almost no one interviewed had ever heard of acute nicotine poisoning or received information about how to protect themselves. “You fall sick, but you don’t know what it is,” said one 43-year-old farmer. Children and adults interviewed also handled toxic pesticides, often without proper protective equipment. Others were exposed to pesticides while someone else applied them nearby.

Human Rights Watch also found that some workers on large-scale farms worked excessive hours without overtime compensation, or that their wages were withheld for weeks or months, in violation of Zimbabwean labor law and regulations. Some workers said they were paid less than they were owed or promised, without explanation. A cash shortage in recent years has crippled Zimbabwe’s economy.

There are no agriculture-specific health and safety protections in Zimbabwean law or regulations, though the government is working with trade unions and other groups to develop occupational safety and health regulations for agriculture.

Zimbabwe has just 120 labor inspectors for the whole country. Farmworker union organizers told Human Rights Watch that they were concerned that the government lacked the resources and personnel for effective labor inspections.

“People we interviewed were shocked when they heard about how dangerous tobacco work is and were anxious to learn how to protect themselves, their children and their workers,” Wurth said. “The ‘golden leaf’ will only live up to its name when the authorities and tobacco companies confront the serious human rights problems on tobacco farms.”

Quotes from the report

“I hope that my children will go back to school, and become better people, because they can’t do that working in tobacco farming. Tobacco growing is a very difficult field. It makes one grow old before their time.”

– “Anne,” 36, tobacco worker and mother of three child tobacco workers, Mashonaland Central

“When we’re hanging tobacco, we normally feel weak or vomit, and get a headache and dizziness,”

– “Admire,” 43, small-scale farmer, Manicaland

“I’ve had the experience where after hanging tobacco [in the curing barn], I feel like throwing up. But it’s not just me. Even my little brother and sister – I’ve heard them complain about it.”

– “Daniel,” 23, small-scale farmer, Manicaland

“We take the chemical and put it in the water. We carry the knapsack on our backs and start to spray. I feel like vomiting because the chemical smells very bad.”

– “Mercy,” 12, tobacco worker, Mashonaland Cental, describing handling pesticides

“Every time they spray, people go home sick.”

– “Rufaro,” 15, tobacco worker, Mashonaland Central, describing pesticide spraying on farms

“During tobacco season, particularly curing time, I always have chest pains and coughing. We normally share our bedroom with cured tobacco, and the air isn’t good. It’s not safe. I also feel dizzy and have headaches.”

– “Moses,” 18, tobacco worker, Mashonaland West

“During grading, you’re sneezing and having trouble breathing. It’s the smell of the tobacco. Once it hits you it’s like you’ve been burned.”

– “Fungai,” 16, tobacco worker, Mashonaland Central

“It causes a lot of absenteeism. You see right from the onset of the tobacco growing season these children start being absent…. You find out of 63 days of the term, a child is coming 15 to 24 days only.”

– “Joseph,” grade 5 teacher, Mashonaland West

“The way I’m growing up is not a good starting point.”

– “Prosper,” 13, tobacco worker, Mashonaland Central